There is a clear, forceful scene with sufficient symbolic force for it to be called the point of departure of my story. It would have taken place in around 1971 or 1972, a little after we had moved to the city of Santa Fe from a nearby town called Gálvez, where I spent my entire childhood. Gálvez is a small town out in the country, in the middle of what some historians call the Immigrant Pampa, the area where at the end of the nineteenth century the first agricultural and cattle-raising establishments were founded. It was mostly settled by immigrants of Italian and Swiss-German origin.

I must have been about eleven or twelve years old. In one of my first exploratory incursions into my new neighborhood, I come upon the club that my sister and I had joined. The Regatta Club of Santa Fe. A venerable club. Very traditional. I see myself going in and out of the dressing rooms, the halls filled with photos, banners, trophies, the enormous storage sheds with the typical wooden boats, the gymnasiums… Then, suddenly, I come upon a skating class out on a large terrace overlooking the lagoon. I remember the scene perfectly. It was in silhouette, against the backdrop of the red sun of a summer afternoon: the instructor and a couple of young boys wearing black leather skates, and young girls wearing white ones, with their mothers waiting off to the side.

Something caught my fancy. Perhaps it was the harmony of the movements. I don’t know. I can’t grasp—perhaps I don’t want to—the exact shape of my desire. But I know for sure that I wanted to be part of this troupe. When I got back home, undoubtedly at the dinner table, I told my father that I wanted to sign up for the skating classes. His answer was automatic. Direct. I must admit that it was not biting or aggressive: he said that he thought it was not a good idea, that skating was for girls, for women. I didn’t respond. I accepted it. He didn’t have to do much to convince me.

In a way, that incident could be seen as the beginning of a difficult youth. At least on the level of feeling, everything went wrong in the realms of love and sport. I tried, without success, to join the rugby team at school; I never liked soccer; I had the briefest of experiences with basketball that I’d rather not go into; a little bit of tennis at the Jockey Club, where even though I played quite well, I felt left out. Perhaps because I felt I did not belong to that social group. Perhaps I made up being excluded in order to feel the pleasure of suffering or simply due to my early inclination to tell stories from the margins, from the point of view of the weakest.

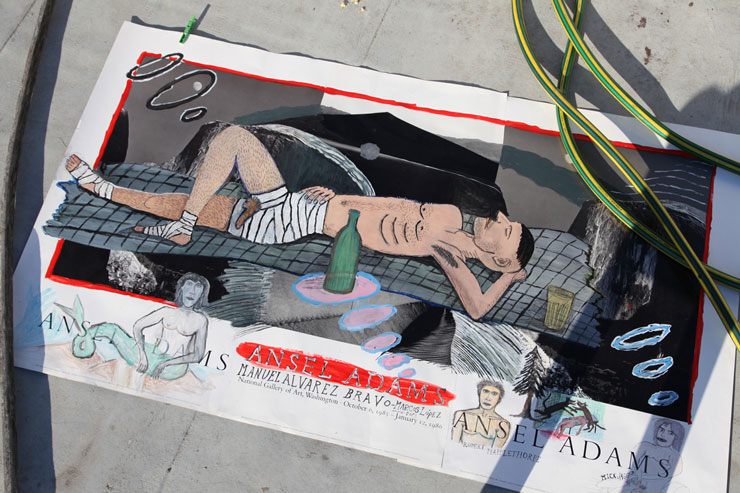

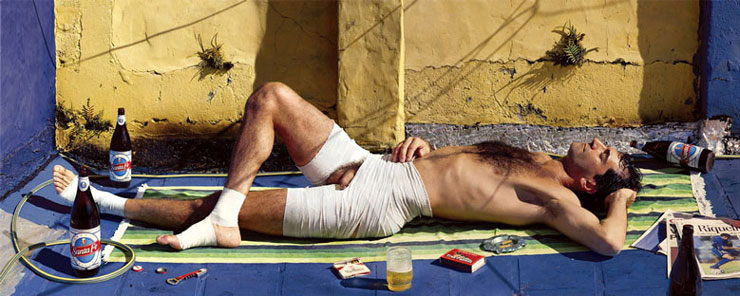

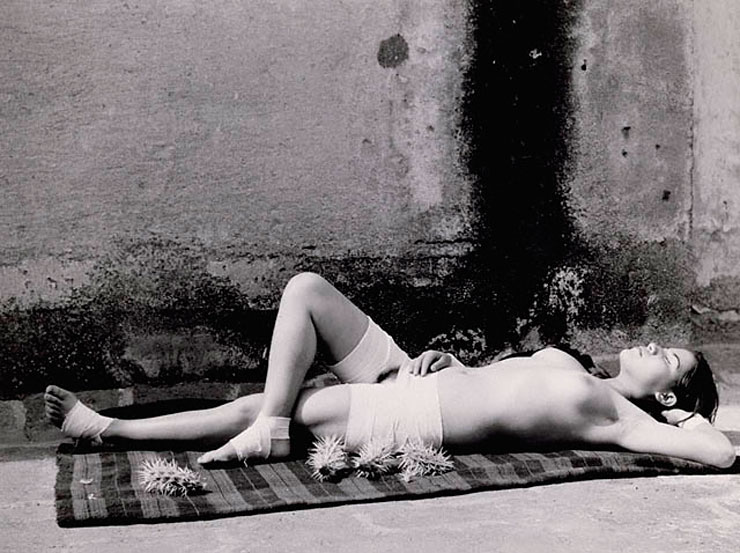

The dramatic structure was perfect. A script of iron could not fail. You won’t let me skate? Just look what I’m going to do with “The Good Reputation Sleeping.” There is no better way to take revenge on one’s father and all the gym teachers and sports trainers I ever met than by going directly to the father’s father. The untouchable master of Latin American photography: Manuel Álvarez Bravo.

Now you’ll see: I’m not only going to change your pretty Aztec damsel into a man, but I am going to invent a sweaty, lazy, drunk Latin Lover who is proud of being an object of masculine and feminine desire. Moreover, making the most of this arrogant digital age, I am going to use Photoshop to enlarge his cock a few centimeters. I am going to give up my systematic and steadfast use of black and white, an almost religious devotion for more than fifteen years. And I am going to recycle the image in the festive and carnivalesque code of Pop Latino. After all, I invented it and I can use it however I want.

You calm down in time. Besides, you’ve got to go on. I was taught to believe in honesty and hard work. I had to make myself strong in a world of men: drinking wine around the table after a barbecue, listening to crude jokes, when all I wanted to do was write a prayer for a sleeping child. Make him laugh. Give him my warmth so that he could dream on. That’s why I write. To change the subject. To talk about the same thing. To give myself the luxury of contradicting myself in the same text fifteen minutes later. To put into words the images that were not meant to be.

In time, you learn to set irony aside and open yourself up to tenderness. After all, revenge is like a game. A creative resource. The truth of the matter is that my Dad knows I love him a lot and that in the end it didn’t matter much to me if I skated or not.

Marcos López